Divided Worlds, 2018

Art Gallery of South Australia

I was part of the AGSA Biennale ‘Divided Worlds’ currated by Erica Green.

Catalogue excerpt:

There is a certain power to the wandering mind. It affords us the ability to escape the limitations of the body and the present, and travel to a distant time and place. We start as children, building and occupying daydream worlds as a way of stepping outside reality, even if just for a moment. In literature, these reveries are woven into words: authors of fantasy invite their readers into a fully formed universe of their making. It is in this way that artist David Booth works, devoting his life to world building through art.

Better known by the nom de guerre Ghostpatrol, Booth first entered his ‘other place’ growing up in Hobart in the 1980s. Feeling geographically isolated, he set about constructing a universe of his mind’s making. Through drawings, paintings and sculpture, he posited a fictional space occupied by characters and scenes from across history, fantasy, nature and his own lived experience. The freedom attached to illustration meant that time and place knew no bounds: characters from Star Wars cohabited with Japanese anime and, later, Corita Kent encountered Henri Matisse.

Now working from his studio in Melbourne, Booth tirelessly builds on his imagined space. He returns to the realm first visited as a child every time he picks up a pen or brush. By now he knows it well, acknowledging that he has spent ‘more time there than on Earth’.

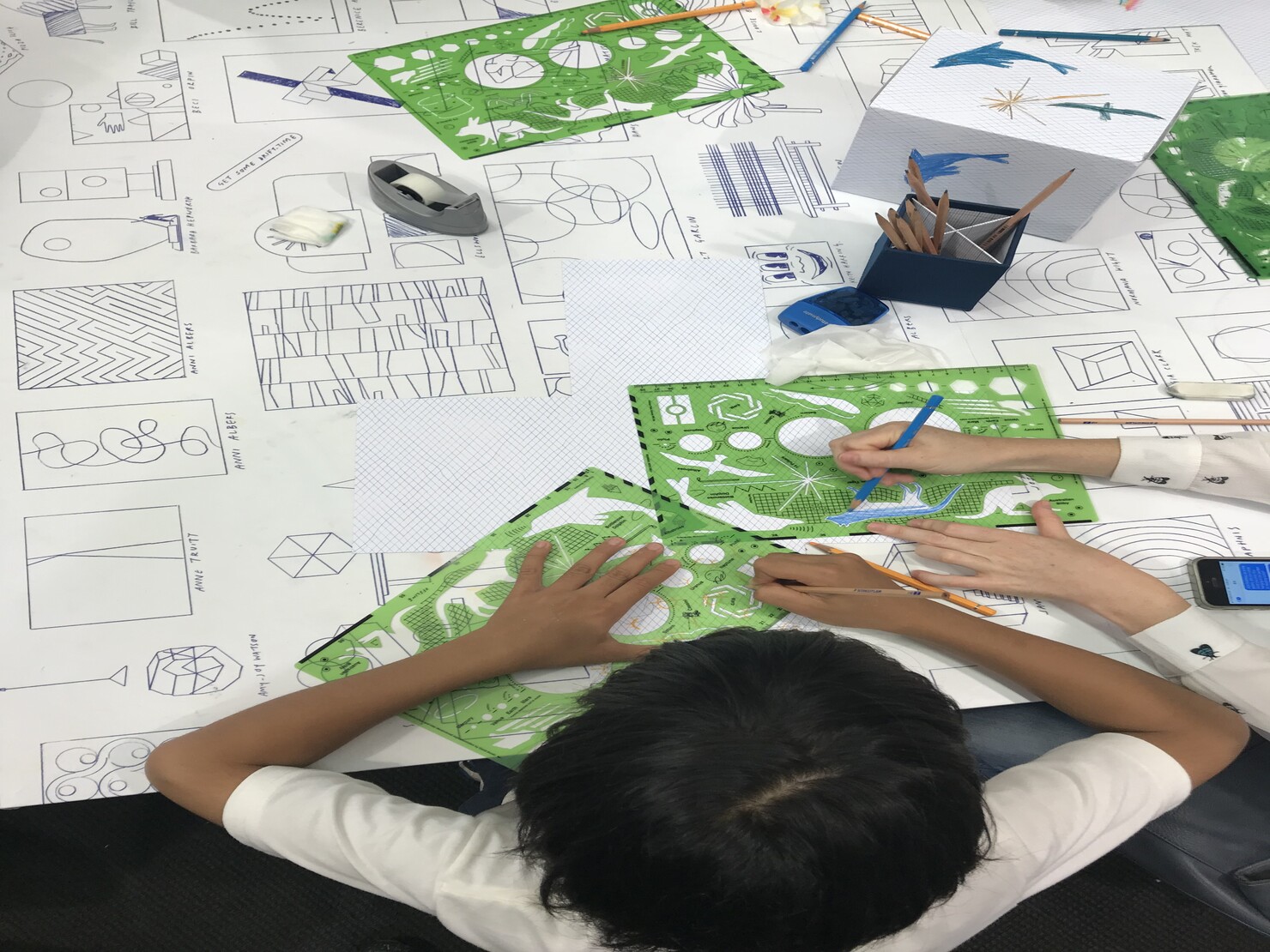

For the 2018 Adelaide Biennial, Booth brings his world into contact with ours. His universe sweeps across the Art Gallery of South Australia walls, inviting visitors to momentarily relax the boundaries between fact and fiction by conflating elements from the two. For audience and artist alike, the Ghostpatrol universe is familiar and inviting, with pale washes of colour punctuated by vivid figures. Densely populated landscapes hum with activity and the artist can be seen in various guises leading a joyous carnival procession across the gallery walls. Booth describes seeing his imagined world so clearly that he can walk around in it as an avatar would a video game. With each turn, an admired figure, artwork or idea is revealed.

Like Australian artist Pip & Pop, Booth presents a hyper-Zen garden for the twenty-first century. His is an ahistorical and apolitical site of refuge, a harmonious vision of life where pop and mass culture reign supreme. Resonating with Hieronymus Bosch’s infamous paradise in perpetuity, with the final scenes of destruction and despair kept at bay.

But as with all daydream worlds, this is not pure escape. For Booth, art making is meditation: rather than a means to leave the confines of reality, it is a way of teasing apart the mess of his every day and piecing it comfortably back together. The cathartic possibilities of daydreaming were well observed by another world builder, Dr. Seuss, who opined that ‘fantasy is a necessary ingredient in living … it enables you to laugh at life’s realities’.

As we float through Booth’s cosmos, the words of J.R.R. Tolkien may be called to mind, offering us a reminder that not all minds that wander are lost.

Joanna Kitto, 2017